|

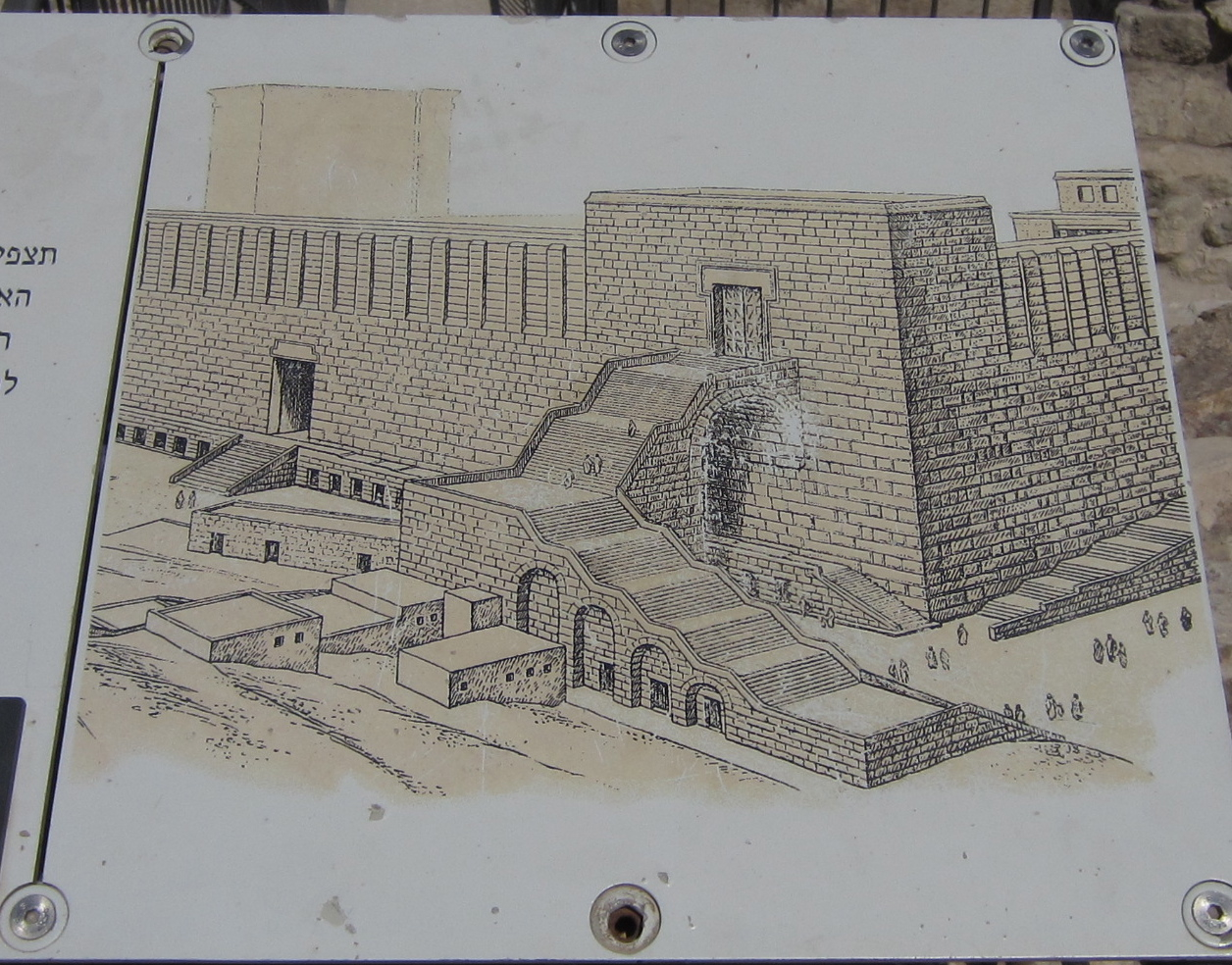

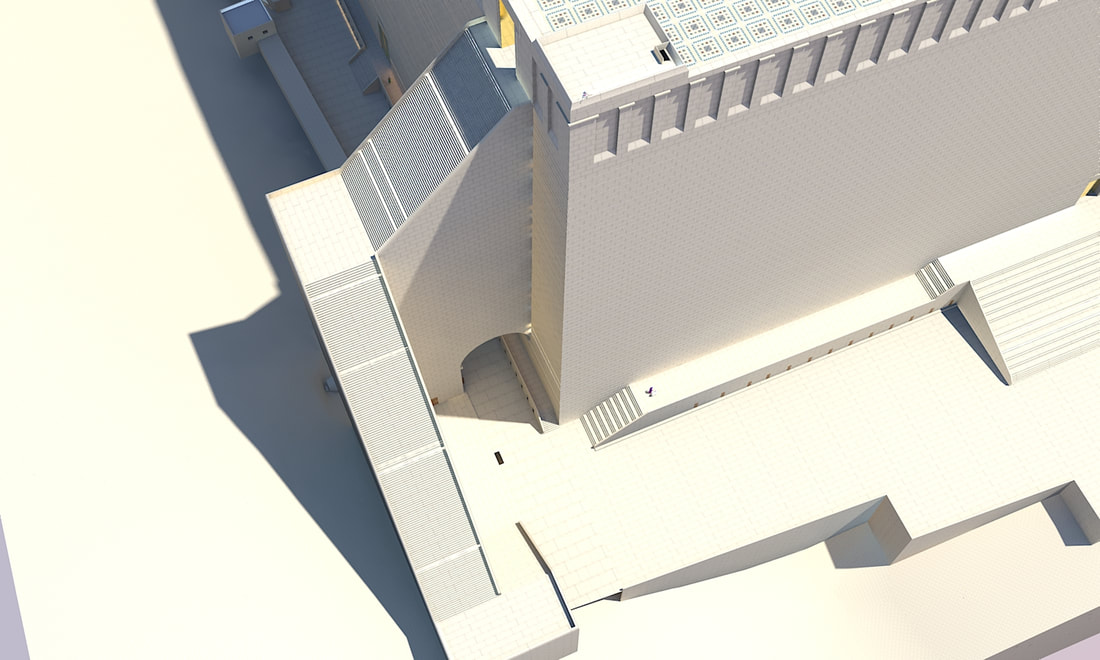

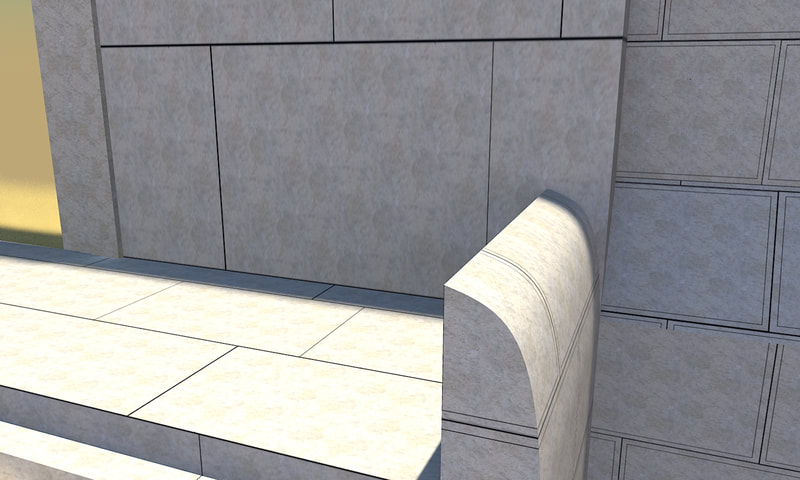

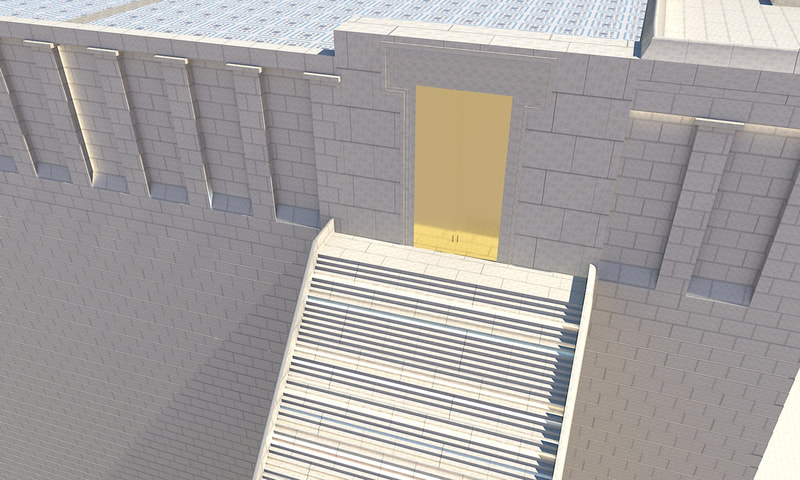

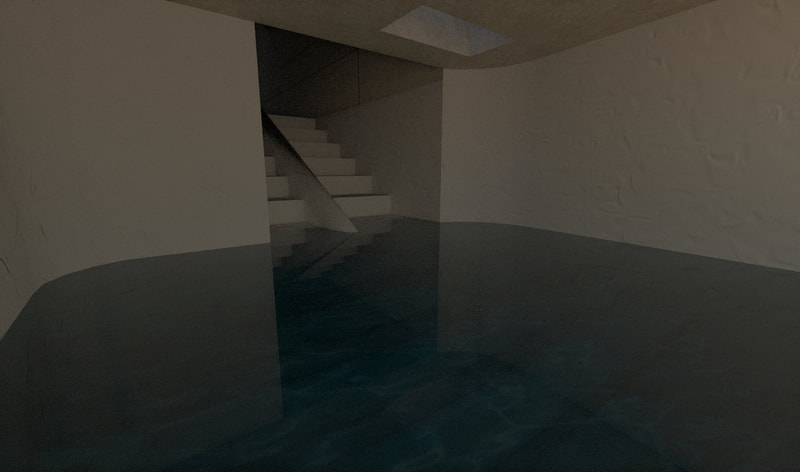

At the southern corner of the Western wall, remains of an arch can be seen. In the times of the Beis Hamikdash, this arch supported a grand staircase which led up to the Har Habayis. It is mentioned by Josephus (Antiquities 15:11:5), who writes: Now in the western quarters of the enclosure of the temple there were four gates; the first led to the king's palace, and went to a passage over the intermediate valley; two more led to the suburbs of the city; and the last led to the other part of the city, where the road descended down into the valley by a great number of steps, and thence up again by the ascent. This arch is named after the American scholar Edward Robinson, who was the first to notice the arch's remains in 1838. He identified the arch with the bridge that Josephus writes led to the upper city (Antiquities 15:11:5). During his investigations of 1867–1870, Charles Warren noted the presence of a large pier west of the wall. Warren concluded this was but one of many supports for a supposed series of arches supporting a bridge spanning the valley. He subsequently dug a series of seven shafts to the west at regular intervals, but found no evidence of additional piers. He therefore concluded that the bridge was not here, but by Wilson's arch, and this arch supported a grand staircase. However, this opinion was not accepted by most other archeologists and researchers, and it was still the accepted opinion that there was a bridge here, until the 1970's. Only during Benjamin Mazar's excavations between 1968 and 1977 was it discovered that the pier was in fact the western support of a single great arch. Many steps were found in the area, and it was concluded that Robinson's arch supported a grand staircase. During excavations near this arch, fragments of the decorative molding of the doorframe of the gate on top of this arch were found. Also found were many steps, as well as stone railings, 40 centimeters thick, which on the outer side are rounded at the top. This arch is located 12 meters (39 feet) away from the southern corner of the wall, and it is 15.5 meters (50 ft 10 in) wide. The arch springs at a level of 727.6 m (2387 ft 5 in) above sea level. Only the three lowest stone courses of the arch are still standing. The bottom course has five stones, the second course has two stones, and the third course has three stones. (Some people say the middle course has three stones, however Eilat Mazar says that the two southern stones of this course are really one big stone, 14.27 m (45.6 ft) long, but it has a vertical crack in the center, so it looks like two stones.) Under the arch is a row of impost stones, stones that project a lot from the wall, giving the impression of a row of teeth (this architectural feature is therefore called dentils). There are ten stones, most of them squarish in shape, but the southernmost one is rectangular. There have been some theories which say that the dentils were employed as part of a system used to support wooden forms used during construction. However, archaeologists have noted that in this region of limited forests it is much more likely that an earthen mound, rather than expensive wood, was used to support the form on which the arch was constructed. They therefore say that the dentils were a decorative element, built to draw attention to the springing of the arch. (Dentils was actually a common decorative element employed in the area at that time.) 12.8 meters (42 feet) away from the wall is the pier of the arch. This pier is 15.35 m (50 ft 4 in) long. There are four rooms in it, each one being 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in) wide, 2.40 m (7 ft 10 in) deep, and 2.15 m (7 ft) high. The stones of the pier have the Herodian margin drafts, like the walls of the Har Habayis. Based on the number of coins and stone weights found in the pier, it is clear that they served as shops. On top of the entrances to the store are lintel stones, on top of which are remains of four small relieving arches. A relieving arch is an arch built over a lintel to take off the weight of the building above it. The round opening under the arch was sealed by a small stone, most probably in order to keep out small animals and birds. Running along these shops is the western curb of the street, and the floors of the shops are on the same level as the curb. This curb continues running to the south past the pier, and since there are no buildings directly there, a small square is formed. Behind these stores the pier extended around 17 m (55 ft 9 in) further to the west, and had four rooms, two in the south and two in the north. The southeastern room opens to the area south of the pier, and it has another door in its western wall to the southwest room. Both of these rooms have a mikveh in them, the eastern one's mikveh is very small, and is located right next to the door. The western room's mikveh is bigger, and it has a drainage channel cut into its floor. The two northern rooms each have a door on their northern side to the southern part of the stepped street there (discussed further in this article). The western one has an opening in its western wall with steps leading down to a mikveh located in a cave. The walls of this mikveh are plastered, and there is a small stone separator in the center of the stairs, separating the people going down into the mikveh from the tahor people coming out, so they don't touch each other and become tamey again. These steps have a landing in them, probably so shorter people could use the mikveh, or for when the water level was high. In the ceiling of the cave is a square hole, probably to allow the rainwater to come into the Mikveh. To the south of the pier, running at right angles to it, remains of four vaults were found during Benjamin Mazar's excavation. The walls that supported the vaults are spaced with 5 m (15 ft) between one and the next. These vaults progressively rise to the north, and it was assumed that these vaults supported the staircase leading to the gate on top of the arch. (A few steps were in fact found still in place on the southernmost of these walls.) However, since the rise of the vaults are not as much as the rise of the seps, it was decided that there were landings in this staircase. This works fine with the standard archeological opinion that the Har Habayis was always the same height as it is now. However, in a previous post I have shown that based on the Gemara, and Josephus, the Har Habayis used to be much taller. This creates a small problem, because if you make the steps directly on the vaults with landings, like the standard opinion is, then the staircase cannot reach the top of the Har Habayis! (Also, even if you don't make landings, based on the level of the stairs that were found, the staircase could not have reached the top of the Har Habayis.) This, however, leads us with a question what the vaults were for. My theory is that there was another flight of stairs, in the structure supporting the main flight, and this staircase rested on the vaults. This staircase might have given access to a second floor of the pier, or it might have led to underground spaces under the Har Habayis. The first possibility seems more likely, as they could have made an entrance to the underground area, (if there was one here,) from Barclay's gate's tunnel. Josephus writes that after going down the flight of stairs by Robinson's arch, there was a street going up to the western hill of Yerushalayim. [In Antiquities 15:11:5 he writes: the road descended down into the valley by a great number of steps, and thence up again by the ascent (hill). In Sefer Yosifun (chapter 55), he also writes about this street, writing "and one went down with steps to the valley, and from there it turned and went up to the city" (והאחד הולך ויורד במעלות אל העמק ומשם סובב ועולה אל העיר).] This street has been discovered, it is on the north side of the pier, and has steps rising on vaults to the west. After ascending a few steps, the street gets divided into two by a wall, with the southern portion, which has less steps, leading to the two rooms under the pier.

reference

Ben-Dov, Meir. In the Shadow of the Temple: The Discovery of Ancient Jerusalem. Israel: Harper & Row, 1985. Gibson, Shimon. “Archival Notes on Robinson's Arch and the Temple Mount/Haram Al-Sharif in Jerusalem.” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 153, no. 3 (2020): 222–43. doi:10.1080/00310328.2020.1805907. Mazar, Benjamin. “The Excavations in the Old City of Jerusalem Near the Temple Mount — Second Preliminary Report, 1969—70 Seasons / החפירות הארכיאולוגיות ליד הר-הבית: סקירה שנייה, עונות תשכ"ט—תש"ל.” Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies / ארץ-ישראל: מחקרים בידיעת הארץ ועתיקותיה י (1971): 1–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23619371. Mazar, Eilat., Shalev, Yiftah. The Walls of the Temple Mount. Israel: Shoham Academic Research and Publication, 2011. (quoted here) Ritmeyer, Leen. The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Israel: Carta, 2006. Ronny Reich. “The Construction and Destruction of Robinson’s Arch / בניינה וחורבנה של קשת רובינסון בהר הבית שבירושלים.” Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies / ארץ-ישראל: מחקרים בידיעת הארץ ועתיקותיה לא (2015): 398–407. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24433079. Wikipedia contributors, 'Robinson's Arch', Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 13 February 2022, 12:20 UTC, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Robinson%27s_Arch&oldid=1071601630> [accessed 13 April 2022]

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Website updatesI have added a new lego model of the Third Beis Hamikdash, with pictures and a video in the lego gallery. Categories

All

Archives

February 2024

AuthorMy name is Mendel Lewis. Hashem said to Yechezkel, "Its reading in the Torah is as great as its building. Go and say it to them, and they will occupy themselves to read the form of it in the Torah. And in reward for its reading, that they occupy themselves to read about it, I count it for them as if they were occupied with the building of it. (Tanchuma tzav 14) |

- Beis Hamikdash posts

-

sources

- Mishnayos Middos >

- Gemarah

- Rambam >

- Rishonim

- Sha'alos Uteshuvos HaRaDVaZ

- Shiltey Hagibborim

- Ma'aseh Choshev

- Chanukas Habayis (both) and biur Maharam Kazis on middos

- diagrams >

- Tavnis Heichal

- Be'er Hagolah

- Binyan Ariel

- Shevet Yehudah

- other

- Braisa D'Meleches Hamishkan

- Third Beis Hamikdash sefarim

- from Josephus-יוסיפון >

- קובץ מעלין בקדש

- Kuntres Klei Hamikdash

- Gallery

- videos

- 1st Beis Hamikdash

- 3rd Beis Hamikdash

- virtual walkthroughs

- 3d models

- Lego Gallery

- diagram of Mizbeach

- contact

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed